Neither War nor Peace

Irish Neutrality 1939-1946

by Nick Brazil

A state of emergency is declared

One of the least publicised aspects of The Second World War was the rather surrealistic situation that Ireland found itself in during hostilities. The day after Germany marched into Poland, the Irish Parliament sat in emergency session. What was to be decided was whether or not Ireland would stay out of the war. Virtually all members of the Dail voted for Ireland to remain neutral with one exception. James Dillon, the Fine Gael member for Donegal unsuccessfully urged the Irish Government to support the Allies. An ardent anti-Nazi, Dillon eventually quit Fine Gael in 1942 over its support for Ireland’s neutrality.

On 2nd September 1939 a state of Emergency was declared throughout Ireland and Eamon de Valera affirmed that his country would remain neutral in this conflict. This was a blow to the British Government who believed that when push came to shove, De Valera’s Government would side with the allies against Nazi Germany. It also came soon after the loss of three deep water ports in Ireland that the Royal Navy held onto under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty signed in December 1921. The Chamberlain Government relinquished them in 1938 as part of the deal to end the ruinous Anglo-Irish Trade War that had lasted from 1932 to 1938.

In reality, given Ireland’s long struggle for independence from Britain, it would have been politically impossible for the Government in Dublin not to opt for neutrality at the outbreak of war. With independence only seventeen years old, anti-British feeling in Ireland was still very high. Only a couple of days after war was declared, it was Chamberlain’s effigy that was burned in the streets of Dublin not Hitler’s.

The price of fighting the Nazis

Whilst Ireland was not the only European neutral country in the Second World War, in many respects, it was in a unique situation. For a start, it actually had a land border with the United Kingdom. This was the border that ran from the east to West coast separating the six counties of Northern Ireland from the Republic of Ireland. Fifty thousand of its citizens were also serving in the British armed forces. Of these, nearly five thousand had deserted from Ireland’s own small armed forces to fight Nazism.

Survivors of this latter group would pay a high price for this after the war. On return to Ireland, any member of the Irish forces who had deserted to fight for the allies, lost their rights to state pensions and were banned from government employment. It would not be until 2013, sixty-three years after the war had finished that they were pardoned by the Irish Government.

White stones on the cliff tops

In war and peace, nothing is ever completely black and white. This also proved to be the case with Irish neutrality. Even the word war became taboo in official documentation. Instead, it was referred to as The Emergency. Today, some of the only visible reminders of this uneasy time are the word Eire picked out in white stones on clifftops such as Malin Head at the northernmost point of Ireland. These were placed to inform both allied and Luftwaffe planes they were flying over neutral Irish territory.

The Emergency Powers Act 1939 was also passed by the Dail. This gave the Irish Government sweeping powers of internment, censorship of the press and correspondence. The de Valera government made widespread use of these powers especially against the IRA. This was very controversial since many Irish people felt the Taoiseach (Head of the Government) was turning against his old comrades in the independence struggle.

However, the truth of the matter was that the leaders of the IRA such as Seamus O’Donovan believed an alliance with Germany was the best way to unify the whole of Ireland. On 23rd December 1939, the IRA raided the main ammunition store at The Magazine situated at Phoenix Park in Dublin. In what became known as “The Christmas Raid” a million rounds of ammunition were stolen. It was this that triggered the passing of the Emergency Powers Act the following day.

The S Plan

In January 1939, the IRA declared war on England. Under the title The S Plan (Sabotage Plan), they mounted a bombing campaign throughout the country. As a gesture to “the Celtic Nations” Wales and Scotland were excluded from this campaign. Although the campaign was considered a failure, it killed ten people and injured 96. The S Plan also fell victim to the law of unintended consequences since it helped to forge a close working relationship between the the British and Irish security services. This lasted throughout the war in spite of the neutral status of the Irish State.

As for the IRA, their effectiveness was not considered to be very great throughout the years of The Emergency. Leading Nazi agents such as Herman Gortz also did not have a high regard for the IRA operatives whom he dealt with whilst in Ireland. Nevertheless, Irish Intelligence and its chiefs such as Colonel Dan Bryan, were by no means complacent about the threat the IRA posed to Ireland during the Emergency. This was particularly the case early on in the Emergency immediately after “The Christmas Raid”.

The IRA Chief of Staff Sean Russell also went to Berlin early in the war to explore links with The Abwehr – German Intelligence. Whatever he may have developed in this respect would not reach fruition. On his return to Ireland in a U-boat, he died of a burst gastric ulcer on 14th August 1940. He was buried at sea 100 miles off the Galway coast.

Abwehr spies sent to Ireland

Throughout the Emergency, the Garda (Irish Police) fought a low level war against the IRA which cost the lives of five of their men. A total of six IRA members were executed by the Irish Government mainly for the deaths of those Garda. These executions by De Valera’s Government against members of a movement that fought for Irish independence were highly controversial.

At this time, the Abwehr, German military intelligence, sent a number of spies to Ireland. However, their attempts to collaborate with local IRA cells were abortive. Virtually all of them were also apprehended a short time after landing. In fact, the German intelligence operation in Ireland during the Emergency was a total failure. Abwehr agent Herman Gortz was probably the most successful in evading capture. Parachuted into Ireland in the summer of 1940, he was arrested eighteen months later in November 1941. Released from prison at the end of the war, he committed suicide in May 1947 to avoid deportation to Germany. Apparently, he feared being grabbed by the Soviets once back on German soil.

There was a widespread belief in wartime Britain that neutral Ireland was clandestinely siding with Germany and the Axis Powers. However, this is a misconception that is not born out by the facts. There were many ways in which Ireland actively helped Britain and the allies. Often, this meant violating her strict neutrality status. A good example of this was the aid given to the Eros a British merchantman that had been damaged in an attack by U boat U-48 a hundred miles off the Donegal coast on 14thJune 1940. Not only was she towed to safety in Irish waters by HMS Berkeley, but was repaired whilst under guard by Irish forces at Errarooey Bay, a remote beach on the Donegal coast. Having been repaired, she then continued her journey to Liverpool. Officially, the Irish authorities knew nothing of her cargo of small arms

The Donegal Corridor

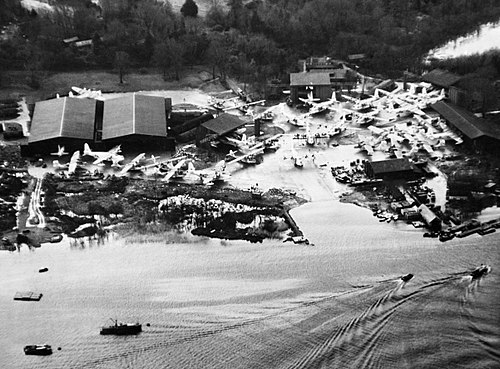

The Donegal Corridor is another example of how Ireland bent the neutrality rules to help the allies. During the Second World War, RAF Flying boats were based at Lough Erne in Northern Ireland. From there, they would fly out across the Atlantic to help protect the Atlantic convoys from U-Boat attack. The shortest route to the Atlantic was across Donegal from Belleek in British territory to Ballyshannon in Ireland. Because of the latter’s neutrality, the RAF planes could not use this four mile route. Instead they had to fly due north and then West. This limited the flying boats’ range, leaving an area in the Atlantic where the convoys were unprotected from U boats. This area was known appropriately as The Black Gap.

As a result of secret talks between Eamon De Valera and Sir John Maffey, representing the British Government, Ireland allowed the RAF Sunderland and Catalina flying boats from Lough Erne to traverse that crucial four mile stretch of neutral territory in Donegal. The value of this arrangement can be judged by the fact that the flying boats from Lough Erne were responsible for sinking nine U boats and seriously damaging many more.

The Irish merchant marine

An MTB of the Irish Marine and Caostguard Service also took part in the Dunkirk Evacuation. On two journeys, it resuced British and French troops from the beaches.

Information from the Irish meteorology station at Blacksod Bay, County Mayo on weather conditions in the Atlantic enabled the Allies to go ahead with the Normandy Landings on D-Day. In addition to this, the security services of both Ireland and Britain had a very close working relationship throughout the whole period of the war.

Nevertheless, on a government level, the relationship between the two countries was not an easy one. In the case of Churchill and de Valera this was particularly fractious.

Whilst the neutrality policy of the de Valera Government had overwhelming support amongst the population, it undoubtedly came with consequences. At the outbreak of war, Ireland found herself largely cut off from the rest of the world. Many of the ships from countries such as America that had brought in most of the imports, would no longer sail to Irish ports since they were considered to be in an active war zone.

With only seventy-one ships in her merchant marine, Ireland was faced with a daunting task to keep the country and populace supplied with imports such as maize, fruit, coal and oil. The sailors of the tiny fleet performed their dangerous job with outstanding bravery and loss of life. In spite of the fact that Irish merchantmen were clearly marked as neutrals, at least twenty were sunk mainly by German U boats, planes and warships. At least twenty per cent of the Irish merchant seamen perished as a result of this. Unlike merchantmen from other nations, Irish ships stopped to pick up survivors of sinking ships. This saved the lives of five hundred and thirty four seamen.

The Luftwaffe bombs Ireland

As well as rationing, the war came to Ireland in more deadly ways. On 26th August 1940, the Luftwaffe bombed a creamery in the village of Campile in County Wexford. At about lunchtime, a single Luftwaffe bomber made two runs over the Shelburne Co-operative Creamery. The single bomb dropped on the first run failed to explode whilst the three others all detonated in the restaurant area of the plant killing three women employees. The most common explanation for this raid was that the German bomber had become lost and the crew thought they were bombing a target in Wales. Since it was in broad daylight, navigational error of that magnitude seems unlikely. A more sinister explanation by some historians is that the bombing was a warning by the Germans to neutral Ireland not to supply Great Britain with food. In 1943, the German Government paid £9,000 in compensation for the raid.

In fact, this was neither the first nor the last time the Luftwaffe would bomb Ireland. Six days before the Campile bombing, a Luftwaffe plane strafed the lighthouse on Blackrock Island. Nobody was injured in this attack. Other bombings followed this. Between 20th December 1940 and early January 1941, there were about five separate incidents of Luftwaffe bombs being dropped on residential areas in the vicinity of of Dublin leaving twenty people injured and three dead.

In April and May 1941, the Luftwaffe bombed Belfast killing a total of 1000 people. Responding to a request for fire tenders from Northern Ireland’s Minister for Commerce, the de Valera Government sent thirteen fire engines to help on the night of the heaviest raid on 15th April.

Plans to invade Ireland

Following this, a significant number of German planes bombed the Dublin area of Northside on 31st May 1941. It was the deadliest raid yet with twenty-eight people killed. There were various possible reasons for this bombing including navigational error by the Luftwaffe and a warning by the Germans to the Irish not to help out the Northern Irish (British) with their fire appliances again as they did in The Belfast Blitz.

The Germans were also thought to have bombed Dublin in revenge for Ireland shipping food, such as cattle to Britain. Perhaps the darkest theory was that the British had developed a method of distorting or bending the radar of the German planes sending them off course over neutral Ireland. This was known as “The Battle of the Beams.” Even after so many years the actual reasons for those 1941 raids remain a matter of conjecture.

The bombing underlined the fact that even as an officially neutral country, these were dangerous and uncertain times for Ireland. On 10th May 1940, Britain invaded and occupied Iceland to deny it to the Germans. There was a fear this would also happen to Ireland with either Britain or Germany invading. It is true that the German military probably under the direction of General Leonard Kaupisch drew up a plan to invade Ireland under Operation Green in 1940. However, this was supplementary to the main invasion plan to invade Britain under Operation Sealion.

Unsung heroes of The Emergency

By the same token, during the darkest days of the Second World War, Britain also considered stationing forces on neutral Ireland. The Northern Irish Prime Minister, Lord Graigavon also tried to persuade Churchill to invade Ireland with troops from Scottish and Welsh regiments. He believed these would be more acceptable to the “Celtic” population. However, both of these plans were rejected as unfeasible. A more serious political plan was the 1940 offer by Britain to abolish Partition if Ireland threw its lot in with the allies. How this might have altered post-war Irish history can only now be imagined. As it was, the Irish Government rejected the idea believing Britain could not be victorious against the Nazis. As de Valera put it: “Great Britain could not destroy this colossal German machine”.

Of the many unsung heroes of The Emergency, none performed their duties with greater diligence than the Irish Coastwatching Service. Based in 83 Look Out Posts at 5 – 15 mile intervals along the clifftops of Ireland they kept constant watch on her coast often in atrocious weather conditions. The two man teams of coastwatchers worked around the clock in twelve hour shifts. They recorded everything that went on along that coast. Their LOPs were little more than rudimentary brick shelters. The equipment they had to hand consisted of a pair of binoculars, a log book, telephone and bicycle. Their work was arduous, unglamorous but essential.

As the War drew to a close, the Irish Government insisted on adhering to strict rules of neutrality. This would lead to the most embarrassing incidents of the whole of The Emergency. Even when it was obvious the Axis forces were on the brink of defeat, de Valera’s Government insisted on allowing the German, Italian and Japanese Legations to remain open. On 2nd May 1945, de Valera signed a book of condolence for Adolf Hitler’s death at the German Legation in Dublin. This caused great anger and upset outside Ireland , particularly in the United States.

The legacy of The Emergency

The Emergency did not actually end with the cessation of the Second World War in 1945. In fact, it had a remarkably long tailback. Legislation in the Dail ending it was only passed in 1976. This might not even have occurred then, were it not for the need to replace it with new Emergency laws dealing with the spillover from the Northern Irish Troubles.

Ireland’s neutrality during the Second World War also left it with a long and unwanted political legacy. In 1945, she applied to join the newly founded United Nations. However, her membership was blocked by the Soviet Union until 1955. On 10th December of that year she became its 63rd member. The reason for the Russian objection was that Ireland’s neutrality had prevented the country supporting the Allied cause in The Second World War. However, the United Kingdom always supported Ireland’s application to join.

It was not until 2013 that those 5000 Irish soldiers who had faced such official and social ostracization for fighting for the allies received an official apology and pardon for their action. By that time, many had died and it was too late.

The Emergency was indeed a strange time for Ireland when neutrality often meant being in the cross hairs of war. Not a comfortable place for anyone to be.

© Nick Brazil 2022

About The Author

Nick's latest Book

Available on Amazon

Before Chernobyl – Nuclear Accidents The World has Forgotten

Click to see full BMMHS event listing pages.

Contact us at info@bmmhs.org

Copyright © 2019 bmmhs.org – All Rights Reserved

Images © Nick Brazil