Battle Experience from the 'Forgotten War'; Korea 1950-53

by James Goulty

The Korean War - a brutal and bloody commitment

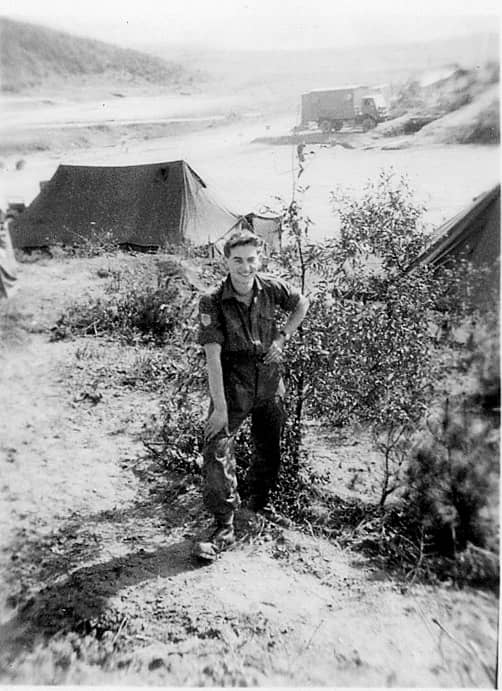

For British troops, the Korean War (25 June 1950- 27 July 1953) was a brutal and bloody commitment. The intensity of the combat experienced, was arguably as tough as it has ever been for the post-war army, even when the Falklands War of 1982 and more recent operations in Afghanistan are considered. According to the Official History, 98 officers and 879 other ranks were either killed in action or died as a result of wounds/accidents. These figures also include personnel classed as missing presumed killed, plus those thought to have been killed while being held as a POW. Likewise, 185 officers and 2,404 other ranks were wounded, many seriously. For example, Harold Davis, who incredibly went on to forge a distinguished career as professional footballer, was raked by enemy machine-gun fire while completing his National Service with the Black Watch, and required two years of hospitalisation to recover from grievous abdominal wounds.

National Servicemen...do us proud

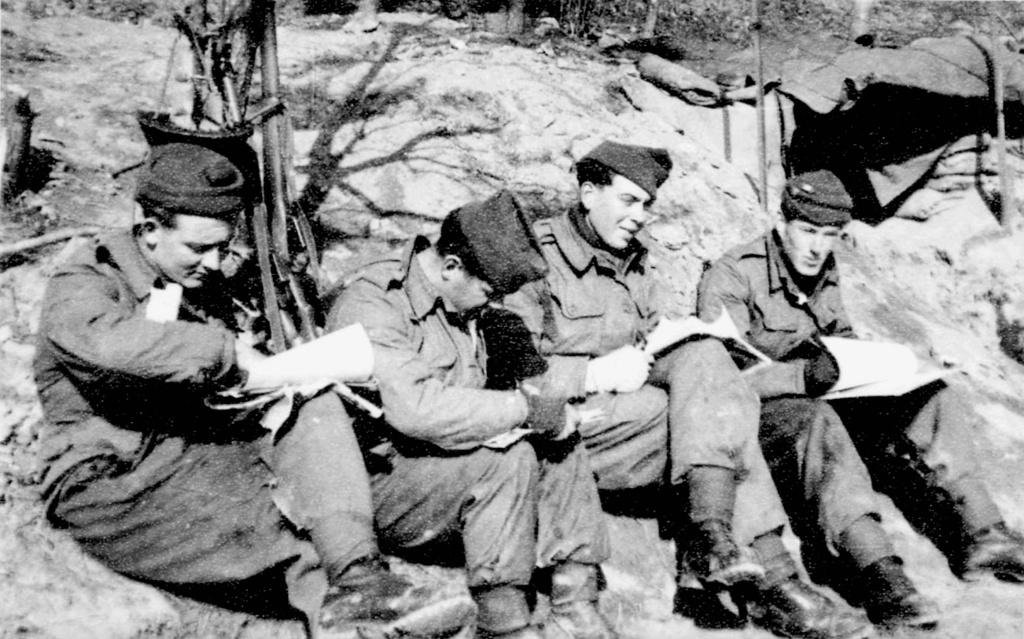

In his memoir, Lieutenant Colonel Colin Mitchell, who served with 1st Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in Korea, observed that ‘soldiers were tested to the limit. If one survived the dangers and rigors of that war, then I believe that one was truly a soldier.’ Yet, it’s salutary to note that unlike during many later conflicts, the army of the 1950s was heavily reliant on National Servicemen (conscripts), young men who didn’t necessarily have any natural aptitude as soldiers, but in many cases performed extremely well. Typically, they served alongside regulars and/or reservists recalled for duty. As Brigadier David Wilson, then a company commander with the Argylls, estimated in his memoir, on arriving in Korea around 40% of his unit were Second World War veterans, whereas, ‘the rest were National Servicemen, who were to do us proud.’

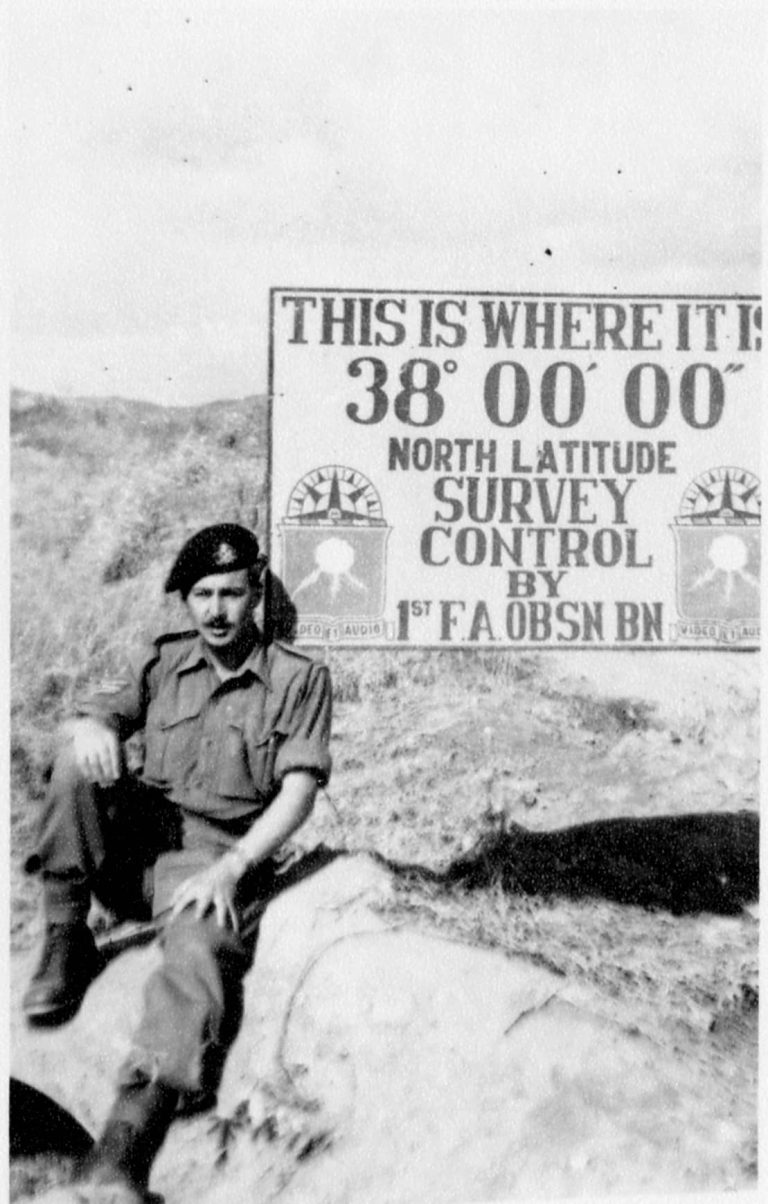

Ultimately 20 British infantry battalions were to see action either during the war and/or in its immediate aftermath upholding the ceasefire, plus 4 armoured regiments and 9 artillery units, together with various supporting units during the same period. These were rotated throughout the theatre so that by late 1953 approximately 100,000 British personnel had experienced some form of Korean service. For the British, the Battle of the Imjin (22-25 April 1951) and those for Hook (18/19 November 1952 and 28/29May 1953) loom large. Equally, there were numerous smaller engagements, which tend to be overlooked, and the gruelling, nerve-wracking grind of night patrolling and raiding that typified the latter phases of the war. Initially conditions were fluid as the fighting ebbed and flowed up and down the Korean peninsula, but by late 1951 the war had bogged down in static mode, broadly along the line of the 38th Parallel (the political divide between the two Koreas) as neither side sought all out victory but preferred to fight to obtain the best possible position on the ground while peace talks made faltering progress.

The Commonwealth Division

British troops served as part of the American led effort backed by the United Nations to counter the North Korean invasion of South Korea that had occurred in June 1950. As well as those from South Korea, America and Britain, combatant units came from Australia, Canada and New Zealand, plus Belgium, Columbia, Ethiopia, France, Greece, the Netherlands (Holland), Luxembourg, the Philippines, Thailand and Turkey.

The understrength 27th Infantry Brigade, consisting of 1st Battalion The Middlesex Regiment and the Argylls was deployed in August/September 1950, and lacked support which was provided by the Americans. Later it was joined by units from Australia and Canada to form 27th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade, and became a more balanced formation. It was replaced in theatre by 28th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade in April 1951, which again had a sizeable British contingent. Contrastingly, 29th Infantry Brigade Group was an all British affair that had originally been Britain’s strategic reserve, and was replete with its own artillery, armour plus various supporting elements, making it akin to ‘mini division.’ All these formations fought under overall American command, an experience that proved both positive and negative. Ultimately, this was one of the many factors that led to the formation of 1st Commonwealth Division in July 1951, which was heavily reliant on the British Army, and witnessed British and Commonwealth troops with a common tactical doctrine being brought together under a British general.

The challenge of information gathering

When Britain entered the Korean War, one of the challenges faced by the War Office, was gathering information from the theatre from British sources, as opposed to that filtered through from the Americans via the British Joint Services Mission in Washington or General MacArthur’s HQ in Tokyo. Consequently, a Battle Experience Questionnaire (BEQ) was devised by the Directorate of Tactical Investigation, largely concerned with issues around training, tactics and the performance of weapons and equipment. It employed a standard set of 10 (later 11) questions, and these were sent to officers returning to Britain from Korea. These were trialled in 1950 on Miles Marston, a company commander from the Argylls, who was leaving the Pusan bridgehead to attend Staff College. Originally from the London Scottish and then an Argyll, he’d spent most of his Second World War with 7th Gurkhas in Italy, before returning to the Argylls. Clearly his experience of Korea was limited, but the War Office deemed that the information he provided was so useful that on returning to Britain he was interrogated by Arms Branches and Schools.

Ultimately, the BEQ programme canvassed the opinions of around 200 officers from a wide variety of backgrounds, not just combatants, but also those from units such as the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, who’d seen service in Korea during 1950-1952. This included youthful regular and National Service subalterns as well as senior officers in their 40s. Notably, this included Brigadier J. F. M. MacDonald, a future major-general and meticulous teetotaller, who commanded 1st Battalion King’s Own Scottish Borderers before replacing the dynamic extrovert Brigadier George Taylor when he was sacked as OC 28th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade. Completed forms were sent to the War Office for analysis by Major P. H. Godsal, and now reside within WO 231 Directorate of Military Training Papers at The National Archives, Kew.

The Battle Experience Questionnaire

Respondents were asked for their name, unit and age, before facing the following questions:

- What battle areas were you in and from what dates?

- In action did you experience any shortcomings in the training you received prior to going into battle?

- What enemy tactics, and/or weapons, took you by surprise or came as something quite unexpected?

- What general tactics were employed by the enemy? Were they orthodox by our teachings?

- Did the enemy possess any arms or equipment to which we had no answer?

- Were we short of any arms or equipment?

- How did the enemy manage to cope with our air superiority?

- What limitations, if any did our equipment impose upon our mobility?

- Were the normal methods of intercommunication satisfactory under all conditions?

- What enemy weapons had the greatest adverse morale effect upon our own troops and why?

In 1952 the following question was added:

Give a couple of tips which you think would help an officer of your rank when he is posted to Korea.

‘Lessons learnt in Burma cover practically every point in how to deal with Chinese...'

Officers with Second World War experience from the Far East likened the North Koreans and Chinese to the Japanese. A major from the Royal Ulster Rifles, advised: ‘Lessons learnt in Burma cover practically every point in how to deal with Chinese, with the addition of training in winter warfare.’ Nonetheless, North Korean and Chinese soldiers proved wily and tenacious opponents. For MacDonald, the enemy exhibited a ‘high standard of patrolling and field craft’ had ‘fanatical courage and endurance’ that ‘were higher than I expected.’ Another officer from the RUR, discovered during 1950-1951 that, ‘quite a large number of the men were surprised at the Chinese night warfare and at their methods of infiltration and at ‘‘noises off’’ trumpets, whistles, gongs, slogans etc.’ Similarly, an officer in the Royal Artillery who served in theatre from November 1950 until November 1951, commented that such noise created uncertainty because ‘you didn’t know what to expect except that an attack was coming. It seemed to give the impression of a ghost like remote control of the battle.’

In attack, the North Korean ‘ability to disperse and concentrate quite large formations at will’ was a shock according to one respondent, especially as intelligence (despite air recce) was ‘unable to keep us informed.’ They favoured infiltration, often relying on ‘disguises’ such as ‘peasant dress,’ and where applicable employed ‘Banzai’ style assaults. Contrastingly, another company commander described, how the Chinese would ‘break contact by day (except during a set piece battle) then a rapid approach march of say 10 miles at dusk, followed by an overwhelming attack at a weak point coupled with secondary infiltrating attacks on a wide front to tie down our reserves. Recces were presumably done sometime in advance and by the use of fifth column.’ These mass attacks came as a surprise. A Reservist Officer with the Gloucestershire Regiment explained that enemy troops ‘seemed to come on quite regardless of casualties. The most experienced soldiers in the unit said they had never come up against anything like it before.’

'..advance in their hordes through their own fire…

According to answers from the Argylls, in defence the North Koreans employed well camouflaged positions and had a penchant for mounting swift counter-attacks. The Chinese made good use of terrain, and sometimes skilfully sited bunkers. The Royal Northumberland Fusiliers found, ‘the reverse features were most strongly held, and in undulating country the base of the forward slopes which covered the reverse crest of the main feature. The high ground and tactically important features were always defended.’

By 1952 the dynamic had changed with the enemy employing significant levels of artillery, often concentrated on a specific point, together with mass attacks. Referencing an action in November 1951, a captain from King’s Shropshire Light Infantry stated, ‘they concentrated artillery from a whole army on our brigade front; then proceeded to put down on us very heavy artillery fire…and actually advance in their hordes through their own fire… Thereby they accepted 30% casualties before they even came to grips.’

‘almost animal cunning.’

On patrols it was common for the Chinese to attempt to use their superior numbers to envelop British patrols by going around both flanks and so cutting them off from friendly lines, and preventing them calling down artillery support. A platoon commander with the Royal Norfolk Regiment reckoned the Communist troops were endowed with ‘almost animal cunning.’ The experience of a major in the Royal Engineers during June 1951-August 1952 provides a case in point: ‘On one occasion enemy replaced detonators of our own mines with small pieces of wood-rendering them harmless.’

Throughout the war the ‘Burp gun,’ sub-machine gun employed by the enemy was viewed with a certain amount of fear owing to its high rate of fire, although at least one officer reckoned this lessened once troops became accustomed to it. Mortars on the other had an ‘adverse effect on morale’ at many times owing to their accuracy, range and because even one bomb could potentially cause many casualties, and it was difficult to hear incoming fire. During 1950-1951 the enemy’s ability to handle self-propelled guns in hilly terrain, and their accuracy proved another shock.

A chronic lack of automatic firepower

Regarding British arms and equipment, a common refrain of many respondents was a chronic lack of automatic firepower to deal with mass attacks, particularly at platoon/section level. This wasn’t confined to the infantry. An officer with 8thKing’s Royal Irish Hussars bluntly commented, ‘one machine gun on the Centurion was NOT enough.’ Likewise, winter clothing in the first year of the war was especially poor, although this did improve later. Another bugbear was the shortage of spare parts for vehicles, and that two wheel drive vehicles were hopeless in the terrain, imposing a severe handicap on mobility. Crucially wireless/radio communications were unpredictable, some officers reporting problems, such as screening by hills, while others were seemingly less hindered by their equipment.

About The Author

James Goulty holds a masters degree and doctorate in military history from the University of Leeds, and has a particular interest in the training and combat experience of ordinary soldiers during the world wars and Korean War.

He has published numerous articles and written 5 books for Pen and Sword Ltd, including The Second World War through Soldiers’ Eyes: British Army Life 1939-1945; and Eyewitness Korea: The Experience of British and American Soldiers in the Korean War 1950-1953.

Click to see full BMMHS event listing pages.

Contact us at info@bmmhs.org

Copyright © 2022 bmmhs.org – All Rights Reserved

Images © James Goulty